James Burke was a spy for the British during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. His exploits read like fiction. He moved with impunity around the highest levels of European society and claimed many of the most notable women as his lovers.

You get the impression from reading the meagre historical sources that he was a braggart, a scoundrel, and vainglorious – to use the vernacular of the day the he p**sed more than he drank. However, he was present at many of the key turning points of the wars against France and Napoleon and played no small part in their defeat, and it’s clear that to have achieved all that he did, he must have been brave, intelligent and very charming.

He was born in Lorient in Brittany in 1771. His father was a Jacobite who served in one of the Irish regiments in French service. James follow this father into the army joined the Regiment de Dillon in 1792. His brother was also in French service and rose to be aide de camp to one of Napoleon’s marshals.

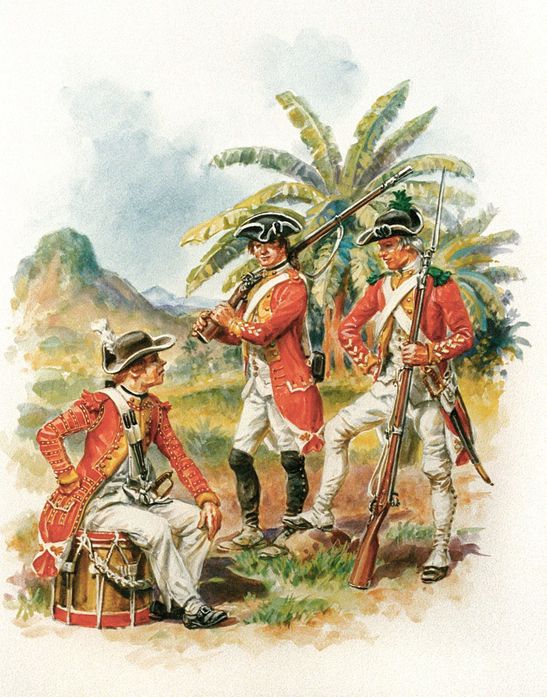

In 1793 Burke was serving with his regiment in Santo Domingo in the Caribbean, when it surrendered to the British. Like many foreign corps they choose to serve new masters rather than face imprisonment in the hulks. Their uniform coats were already red so they didn’t even have to turn them. The regiment, now Dillon’s Regiment, served in Egypt with Abercromby, where they had a reputation as rogues and drunkards. They then went on to serve in the Peninsular under Wellington but Burke didn’t stay with the colours for long.

How and why he became a spy isn’t clear. It may have been his knack for languages, the connections of his brother, an aversion to boredom or an eye for improving his lot in life, but something led him to volunteer for unconventional duties. Whatever it was, he was soon being sent across Europe and working directly for the Duke of York.

In 1804 he was sent further afield. The Spanish colony of Rio de la Plata was providing much of the silver for the French treasury, and the British prime minister Pitt had ambitions to stem the flow of wealth from the new world into French and Spanish coffers. Burke was sent to Buenos Aires to gauge what appetite there was for independence. I used elements of his mission there as inspiration for my second novel, Expect No Safety.

Burke displayed his talent for insinuating himself into society, soon becoming friendly with the Spanish viceroy and even more friendly with Ana Perichon, the wife of an Irish merchant who was his contact in the city. He met with the nascent independence movement in the province and then, after a few months, travelled to Chile and Upper Peru (now Bolivia). Somehow he must have gone a step too far because he was arrested and returned to Buenos Aires as a spy.

He managed to talk his way out of the charge, claiming to be French, but was forced to leave. He did however manage to retain the large collection of minerals that he had amassed, along with two creole horses, three llamas, two alpacas and a brace of vicunas. He even found time to stop at Rio de Janeiro and take a look at a diamond mine. He planned to give the animals to the Duke of York for his menagerie.

He arrived back in Europe in 1806 and immediately sent a detailed plan for an invasion of the Spanish colonies to the government. However, an unauthorised and ultimately disastrous expedition by Commodore Popham with troops from the Cape of Good Hope pre-empted his plan.

Burke was again sent on a tour of Europe to gauge the strength of the few countries still opposing Napoleon. He became the confidant of Prussian general von Blucher and was accepted at the court of Empress Josephine while her husband was absent campaigning.

When French designs turned to Portugal and Spain, Burke was sent to Madrid. He arrived with a letter of introduction to the French ambassador, brother of Josephine’s first husband, from French foreign minister Talleyrand. He established himself as a wealthy merchant from Buenos Aires and, with the help of another relative in the Spanish army, was soon being received at the highest levels of society. He presented a note from the British government to the Spanish prime minister Manuel Godoy, and revealed his identity to King Carlos IV and Queen Maria Luisa warning them of Napoleon’s plan to replace them with one of his kin.

He suggested later that he became intimate with the Queen; whatever the truth of the matter, he was entrusted with letters for their majesties’ daughter Princess Carlota who had fled to Brazil with her husband John, Prince Regent of Portugal.

Back in London he presented his most audacious plan yet to the government. He told them that if they furnished him with forty resolute men and £200,000 for expenses (worth nearly £7M today) he could kidnap Napoleon and return him to England. Sadly the government declined.

Instead he was sent to back to Buenos Aires to see how events in Spain had changed things and whether French agents were active in the city. He stopped in Rio on the way to deliver the letters to Princess Carlota and promptly became her lover. He stayed in Rio for five months, as there was unrest in Buenos Aires, but when eventually he did arrive in the city his reputation preceded him and he was not welcomed by the new viceroy, Liniers, possibly because he had taken Ana Perichon as his mistress too.

Sent back to Rio, he wasn’t welcome there either. Prince John, Carlota’s husband, not unsurprisingly, named him a persona non grata. He left for Europe in the summer of 1809. He popped up briefly in Spain for a while working for Wellington, who even offered him the position of Assistant Quarter Master General, but he declined. He was, however, employed by Wellington’s brother and British Foreign Minister, Maquis Wellesley, and sent on further missions around Europe. He met with Tsar Alexander and Marshall Bernadotte amongst others.

He petitioned for a pension and a knighthood, which he thought was his due, but his requests fell on deaf ears as many of the men he had served had left the government. After 1812 there isn’t much evidence of any more spying missions in the records, so perhaps he returned to ‘proper’ soldiering and the more mundane life of campaigning. He retired from the army in 1826, after 34 years of unconventional and exceptional service.

References

Études Irlandaises 1998 Vol 23. A soldier under two flags. Lt Col. James Florence Burke. Officer Adventurer and Spy.

Secret Service – British Agents in France 1792 – 1815 – Elizabeth Sparrow

Available from Amazon or directly from the publisher Helion, which means I make a little more rather than Amazon getting all the profit!