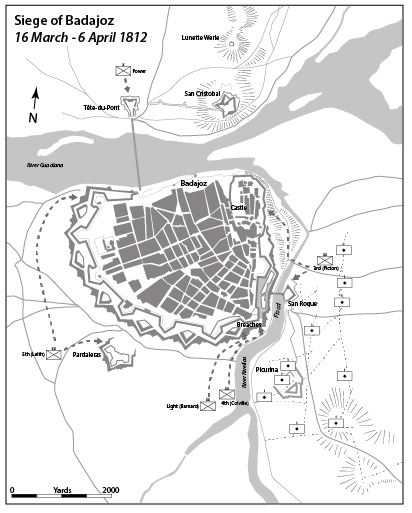

When I started to write Riflemen – my history of the 5/60th Rifles – I also decided that I would draw all my own maps rather than pay for them to be done for me. I have worked in the graphic arts industries for 30 years and can use all the relevant software. I ended up creating over 30 maps, either showing the flow of an entire campaign or the details of a particular battle. For the campaign maps I licensed a detailed map of the Iberian Peninsular and adapted it to what I needed. For the battles is generally used James Wyld’s splendidly titled Maps and Plans, Showing the Principal Movements, Battles & Sieges, in which the British Army was Engaged during the War from 1808 to 1814, in the Spanish Peninsula and the South of France, published in 1840. This outstanding volume of detailed maps was the idea of Wellington’s Quartermaster General Sir George Murray. Murray arranged for Captain Thomas Mitchell to spend four years completing and refining the maps that the QMG’s department had drawn during the war. You can download a copy of the atlas from the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal here. I would redraw the relevant map and then use other sources such as Oman’s A History of the Peninsular War and Colonel Nick Lipscombe’s excellent The Peninsular War Atlas to confirm details of unit posting etc.

I naturally decided to also do my own maps for At the Point of the Bayonet – my forthcoming book on the battles of Arroyomolinos and Almaraz. As both actions occurred within fairly close proximity of each other I decided to try and base my maps plotting the movements of the allied and French troops on a map used at the time, so that I had some hope of showing the actual roads used rather than having to guess if where a road runs now is where the route went 200 years ago. I found that McMaster University in Canada had a collection of three maps from the period available for download and chose Faden’s 1810 Map of Spain and Portugal, which is often mentioned as being used by British officers during the war. I did not expect it to be as accurate as a modern map, of course, but it was only when I started to use it as a template for my own maps did I realise quite how inaccurate it was. I could not use it to reliably represent the distance between places, or even if a village was north, south, east or west of another. Below are the three maps McMasters has, and a modern map from google for comparison.

Accurate maps and route information is obviously crucial for any army and the poor maps available for Spain and Portugal were a major problem for the allied army in the Peninsula. Officers assigned to the QMG’s department were tasked with reconnaissance, route finding and mapping. They roamed far and wide across Spain and Portugal. Topographical intelligence was vital to many of Wellington’s operations, particularly the very rapid advance outflanking the French armies in 1813. The maps and route information obtained by the QMG’s department would be copied by draughtsmen in Lisbon and then distributed to the various headquarters.

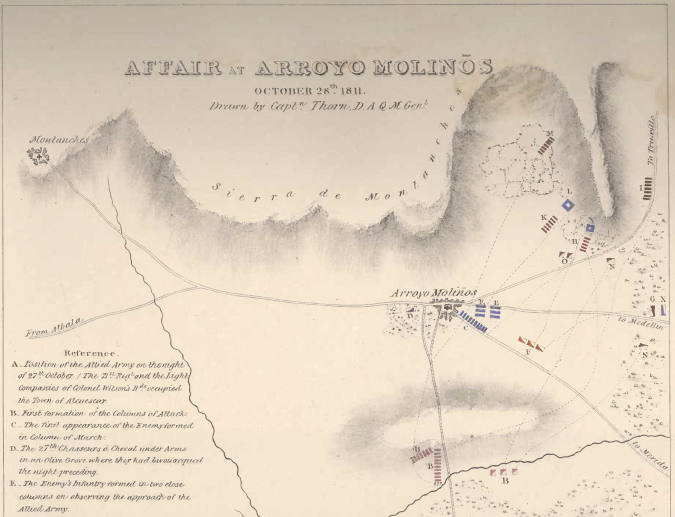

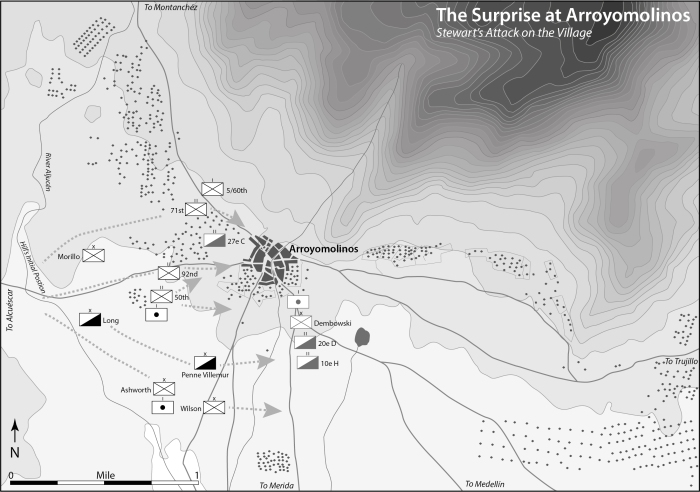

Given the problems with the surviving contemporary maps I decided to use a modern map as a template and then refer to Faden to judge what roads and river crossings were extant at the time. I had a similar problem with the larger scale maps I needed for the battles. It was only after visiting the sites that I realised how badly British maps of the battle represented the topography around Arroyomolinos and Almaraz. Most maps of the crossing at Almaraz do not adequately portray how hilly the surrounding area is, especially the site of Fort Napoleon, and maps of Arroyomolinos distort the line of the hills at the back of the village that played a crucial part in the flow of the battle. Below are sections of a map of the battle included with Hill’s official dispatch, Wyld’s version, a Spanish map done soon after the battle (available here), and a modern map. Some of the differences are due to different orientations of the maps, but the curve and distance from the village to the hills on the right do vary between the maps and it is over that ground that the French retreated and much of the action took place.

Again I decided that the only accurate way to represent the battle was to use a modern map as my base, add some of the details from the Spanish map, and then use all the sources available to place the units and the action as accurately as I could.

No representation of a event that occurred 200 years ago will be perfect, but just as walking the ground is important to understand a battle so to is both understanding the limitations of the maps the commanders were using and also utilising accurate topographical data to create new maps.