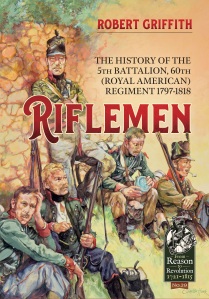

One of the joys of writing Riflemen, my forthcoming history of the 5th Battalion 60th (Royal American) Regiment, has been uncovering the personal stories of the men who served with the battalion. One of the more interesting of those is the story of Johann Leopold von Ingersleben.

The reduction of the Prussian army following defeat by the French and the Treaties of Tilsit led to many Prussian officers seeking employment in British service. Ingersleben was one of those who traveled across the North Sea to Britain, and in common with many other foreign officers at the time he anglicised his name, becoming known as Lewis de Ingersleben. He asked to join the King’s German Legion but in November 1809 the KGL office, unable to find a place for him wrote to General Sir David Dundas, commander-in-chief of the British Army:

‘Lieutenant de Ingersleben late in the Prussian service, who has a very good letter of recommendation from his commanding officer in the Prussian service, but has left it on account of the great reduction which has taken place in that army wishes to be appointed to an Ensigncy in one of the foreign Regiments of Infantry in the British Service.

His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge recommends the request of Mr de Ingersleben to the favourable consideration of the Commander in Chief.’

The Duke of Cambridge was colonel-in-chief of the KGL. Ingersleben was granted a commission as an ensign in the 60th (Royal American) Regiment of Foot on 14 December 1809 and was posted to the 5th Battalion in Portugal. He joined them at Pinhel on 24 July 1810, shortly before the battle of Bussaco. The 5th Battalion had been in the peninsular for more than two years and was divided amongst the various divisions of Wellington’s army. Roughly half of its officers came from the German states. Ingersleben was attached to one of the three companies with the 2nd Division. His unit took part in the long retreat to the Lines of Torres Verdras and then spent the winter watching the French army waste away from disease and starvation.

Following the death of a fellow officer the commander of the 5th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel William Williams, recommended Ingersleben, the senior ensign, for promotion to the vacant lieutenancy. The Duke of Wellington forwarded the recommendation to the commander in chief and Ingersleben was promoted 31 October 1810, but the battalion did not receive confirmation of the promotion until April the following year.

In 1811 as Wellington pushed the French back into Spain the 2nd Division was one of those placed under the command of Marshal Beresford to cover the southern approaches to Portugal. In May Ingersleben was severely wounded at the battle of Albuera where the 2nd Division bore the brunt of the fighting and took heavy losses. He spent time recovering at the fortress town of Elvas before being sent back to England on leave in July. During his time in England he was treated at Laverstock House near Salisbury, by a Dr. William Finch. Laverstock House was a lunatic asylum.

Finch was a pioneer in the treatment of mental health and Laverstock House was well known and often used by the wealthy classes. It was very far removed from the popular vision of a Georgian asylum. The patients were given the time and space to recover in gentle surroundings, with games and hobbies part of the regime. An 1830 prospectus claimed:

‘The situation of Laverstock House is peculiarly eligible. Surrounded by large Gardens and Pleasure Grounds in the midst of a fine and extended Country, it is at once retired and cheerful, and affords the most ample means for indulgence in those exercises which are so essential to the happiness and health of the Patients.’

During his leave Ingersleben also wrote to the commandant of the Foreign Depot that supported the various foreign regiments in the British Army, requesting a position at the port of Harwich which was used to process recruits coming into the country and invalids returning to Europe. He did not get the position and instead in the summer of 1812 reported to the depot to return to his battalion.

Ingersleben was placed in charge of a draft of 192 replacements for the battalion and sailed for Portugal on the Rolla transport at the end of August 1812. Soon after his departure the commandant had to write to Colonel Keane, then commanding the 5th Battalion, to explain that Ingersleben had left Laverstock House ‘whilst in a state of derangement’ without paying his bill and Dr. Finch was requesting that the debt be paid.

Ingersleben arrived back with the battalion in November, during the bitter retreat from Burgos. He was assigned to one of the two companies in the 1st Division. In 1813 he fought at the battle of Vittoria and the siege of San Sebastián, but his story was about to take another twist.

On 10 September 1813 Ingersleben was brought before a general court martial. The charges were:

‘For disobedience of orders on or about the 31st of August 1813 in refusing to withdraw his animals from stables of Lieutenant Wynne, of the same regiment, his superior officer after being ordered to do so, by the said Lieutenant Wynne.

For scandalous and infamous conduct unbecoming the character of an Officer and a Gentlemen, in openly resisting the Authority of his Superior Officer, the said Lieutenant Wynne, and for using opprobrious and disgraceful language to him, and striking him, and further threatening to repeat that assault, to the prejudice of good order and military discipline.’

He pleaded not guilty. Ingersleben had found an empty stable near to where he was quartered and placed his horses inside, not knowing that Wynne had already been putting his own horses there. When Wynne returned and asked Ingersleben to move his horses out Ingerseleben said there was room for both and refused. Wynne said then he would remove Ingersleben’s horses by force. Ingersleben quickly lost his temper, hitting Wynne, calling him ‘a blackguard, coward and Irish rascal’ and saying that if he’d had his sword with him he would have run him through. Wynne called Ingersleben a ‘German Bugger’ and then, apparently, the language became too vulgar to be repeated in court. Lieutenant Hamilton came between the two of them and Ingersleben’s horses were removed by the guard.

Ingersleben was found guilty and sentenced to be cashiered. However, Major General Stopford, president of the court, appealed to Wellington for clemency. Seven members of the court gave Ingersleben character witnesses, praising his good conduct, especially at the battle of Albuera. Wellington wrote back to the court asking them to revise their sentence. He said it had been a private quarrel, that neither had any right to the stable, and that Wynne was himself guilty of a breach of good order. The court reconsidered but thought the wording of charge and the article of war gave them no latitude. However, they did write to Wellington to recommend mercy, which he duly granted.

Reading the transcript of the trial it is clear that Ingersleben’s temper snapped very quickly. This, coupled with his time at Laverstock House, may suggest that he was suffering from what today would be diagnosed as post traumatic stress disorder. The mental health of the soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars is not an area that has been much studied but the records of the 5th Battalion contain a disturbing number of suicides. The battalion was in the peninsular for all six years of the campaign and many of the men would have experienced multiple brutal battles, as well as the everyday hardships of campaigning at the time.

In October Ingersleben exchanged with Lieutenant Peter Van Dyke of the 2nd Kings German Legion Light battalion. It seems likely that it was the easiest way for Ingersleben to remove himself from Wynne, or for the battalion to lessen internal tensions. The 2nd KGL Lights were also in the 1st Division and Ingersleben went on to serve with them through the campaign in the Pyrenees, including the battles of the Nivelle, the Nive, Saint Etienne, and Bayonne. In 1814 Ingersleben went with his battalion to the Netherlands.

When Napoleon returned in 1815 the KGL was part of Wellington’s army for the Waterloo campaign. During the battle the 2nd KGL Lights helped to defend the farmhouse of La Haie Sainte for five hours against repeated French attacks, only retreating when their ammunition ran out. Ingersleben was present at the battle, but it is not clear if he was with his battalion, on the staff, or attached to another unit.

In 1816 when the KGL was disbanded Ingerseleben, by then a brevet captain, went on half-pay. He was still receiving his half-pay in 1824. He died at Meve in West Prussia on the 2nd of November 1834.

My history of the 5/60th – Riflemen is available now from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and other book retailers, or direct from the publisher Helion & Co.