John Downie is one of those characters from history that if they had been created by a historical novelist readers would have thought the writer had gone a little over the top.

Born in Scotland in 1777, the third son to a minor landowning family, he went to the West Indies to make his fortune, which he duly did and then promptly lost it all. He became an officer in a colonial corps in Trinidad, where Brigadier General Thomas Picton was governor and the two became friends.

While in the West Indies Downie also met Francisco de Miranda, a radical advocate of independence for Spain’s South American colonies. Miranda organised an expedition to liberate Venezuela; hiring ships, buying weapons and raising volunteers. The first attempt ended in failure but Miranda escaped and asked for the support of the British. With Royal Navy ships and volunteers from Trinidad, including 60 men under Downie, the rebels tried again. The expedition managed to land successfully this time and capture a battery, but they were soon outnumbered by the Spanish and forced to retreat to their ships.

Miranda sailed for London to garner support for further efforts to free the colonies and Downie went with him. After the failure of his commercial ventures in the Caribbean Downie was in debt and was gaoled for a time. In 1808 Picton secured him a post as an Acting Assistant Commissary (a supply officer) with the British Army in Portugal.

However, the dull life of a commissary was not exciting enough for Downie and he left his post when there was a chance of action near by, much to the exasperation of Sir Arthur Wellesley who wrote in June 1809:

I beg you will let Mr. Downie know that he is a Commissary, and his business at Castello Branco is to collect supplies, and that I am much surprised and highly displeased with him for quitting his station and the business on which he was employed, to move forward to Alcantara, where a few shots were fired, to see what service he could render there; as if he could render any so important as that upon which he was employed by me. I thought he had seen too much service to have been so inconsiderate.

The rebuke seems to have had little effect and Downie soon undertook an unauthorised excursion into French held territory to gather intelligenceDownie. Wellesley censured him again but later wrote a more mollifying letter recognising the value of the intelligence he had supplied, whilst reiterating that he should remain where he was ordered to be.

At about the same time fellow commissary August Schaumann encountered Downie at the head of a party of 40 men of the 4th Dragoons, an episode Schaumann related in his occasionally unreliable memoir. He describes Downie: ‘Over his commissary’s uniform he wore a heavy dragoon’s pouch-belt, and carried a loaded carbine at full cock in his hand.’ And then goes on to relate how the two commissaries interrogated a couple of French prisoners:

It was a funny sight to see the bony six-footer, Downie, astride a chair, now flourishing a long Spanish cane angrily in the air, and then allowing it to rest coaxingly on the prisoner’s shoulder, while ever and anon he exclaimed: ‘Do you hear, my friend, how the crowd are raving outside. Confess, or we will let you loose, and then you will immediately have fifty daggers in your body.’

The prisoners doubted that the commissaries would ever do such a thing but nevertheless told them that the French would attack the allied army at Talavera the next day.

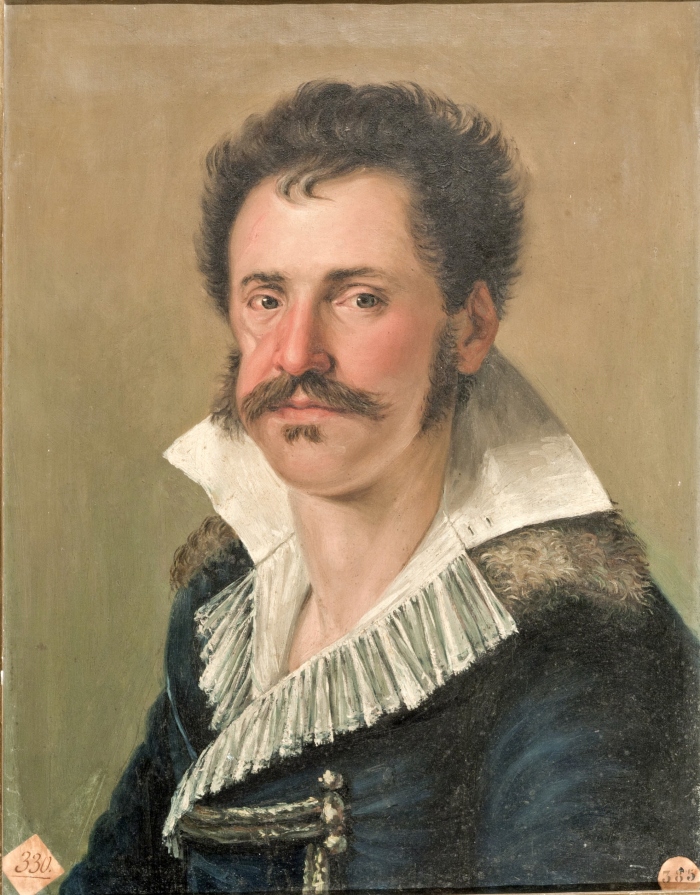

Wellington shortly afterwards recommended his position as an acting Assistant Commissary be made permanent, stating that ‘Mr. Downie has been employed on duties which belong to a Deputy Commissary rather than to an Acting Assistant’ Wellington later referred to Downie as ‘very active and intelligent’ when he sent him to serve under Brigadier General Craufurd of the Light Division. Another officer described Downie as a ‘tall and particulary handsome fellow’ and also brave ‘with a dash of Don Quixotism in his valour.’

In the spring of 1810 Downie, still restless, began to accompany guerrilla bands in skirmishes around Badajoz. In July 1810 he formerly joined the Spanish forces with the rank of colonel. Wellington once said to Downie that he was Spanish ‘down to the shirt’ to which Downie replied ‘It goes much deeper than that, my Lord.’

Downie had proposed raising a mixed regiment of cavalry and infantry from the province of Extremadura. He lobbied Wellington, badgered the Spanish juntas, and during a period back in London cajoled the British government. His tactics seemed to have been variations on the age-old strategy beloved by many children of going to each parent and saying that the other said they could. Eventually he obtained permission to form the Legión Extremeña.

He hoped to build upon regional pride by creating a 16th Century style uniform that harked back to the days of the conquistadors Pizarro and Cortés, both of whom came from the province. Recruitment for the legion was slow, partly due to the poverty of the area, but also becuase of the ridiculous uniform. With few modern weapons available the legion was initially armed with cross-bow, swords, slings, lances and anything else they could find. Downie was even give Pizarro’s own sword to wield against the French and inspire his men, but made to promise that the blade would never fall into the hands of the enemy. Wellington supported Downie with his creation of the legion, urging the British government to supply them with arms and accoutrements, although he did balk at the idea of letting other British officers join the unit and said in a letter to Lord Liverpool, Secretary of State for War, in December 1810:

From the knowledge I have of Mr. Downie’s character and qualifications, I have no doubt whatever that the Spanish cause will derive advantage from his being employed to raise in Estremadura and command a legion, but my approbation of the measure of employing him goes no farther.

Although Mr. Downie has talents and spirit to qualify him for such an employment, it is not fit, in my opinion, to place British officers under his command; and so far to risk the character of the British army in this concern.

The legion was involved in some small skirmishes in the summer of 1811 but their first major operation was Lieutenant General Rowland Hill’s advance into Spain to dislodge a French division from the town of Caceres, which eventually ended in the battle of Arroyomolinos. Moyle Sherer of the 34th Foot recalled encountering the legion:

On the line of march this day, I saw a body of the Estremaduran legion; a corps raised, clothed, and commanded by a General Downie, an Englishman, who had formerly been a commissary in our service. Any thing so whimsical or ridiculous as the dress of this corps, I never beheld: it was meant to be an imitation of the ancient costume of Spain. The turned-up hat, slashed doublet, and short mantle, might have figured very well in the play of Pizarro, or at an exhibition of Astley’s; but in the rude and ready bivouack, they appeared absurd and ill chosen.

Another British officer, Robert Blakeney of the 28th Foot, was also less than complimentary about their performance at Arroyomolinos:

There was also an equestrian Spanish band, clothed like harlequins and commanded by a person once rational, but now bent on charging with his motley crew the hardy and steadily disciplined cavalry of France; and yet, however personally brave their commander, Mr. Commissary Downy, little could be expected from this fantastic and unruly squadron, who displayed neither order nor discipline. Intractable as swine, obstinate as mules and unmanageable as bullocks, they were cut up like rations or dispersed in all directions like a flock of scared sheep.

In the late summer of 1812 the Legion was part of a force that attacked the French held city of Seville. The French had fortified and blockaded a bridge over the river Guadalquivir and two attacks had failed to dislodge them. Downie galloped towards the French, wielding Pizarro’s sword. He was hit in the face by a ball from a round of canister but rode on, despite being badly wounded in the cheek, blinded in one eye and having lost part of an ear. He jumped over the French defences but was surrounded, dragged off his horse and bayonetted. He did, however, manage to throw the sword back to his comrades and so keep his promise. Downie survived his numerous wounds and was later exchanged for 150 French prisoners.

Downie’s adventures became the subject of popular poems celebrating him, many of them written by his own military secretary. When he traveled back to Scotland in 1813 he was feted as a hero, granted the freedom of the city of Glasgow and knighted by the Prince Regent. The Legión Extremeña, with Downie back at its head, took part in the campaign in the Pyrenees and then in the battles as the army crossed into France that winter. Wellington’s Judge-Advocate General Francis Larpent wrote in his journal for 13 October 1813:

The Spaniards were disturbed early yesterday morning about two miles from this, surprised and driven from a redoubt with some loss in prisoners and wounded. I believe, however, that they behaved well afterwards; but a Spanish regiment gave way. That queer playhouse hero, Downie, who was there as a volunteer rallied them and conducted them well but had his horse wounded. He once more exhibited on the Pyrenees the sword of Pizarro, which had so narrow an escape when he was made prisoner in the south.

After the war Downie was promoted to major general in the Spanish army and placed in command of the Alcazar royal palace and fortress in Seville. A post he held until his death in 1826.

Sources:

G. Iglesias-Rogers British Liberators in the Age of Napoleon

M. Sherer, Recollections of the Peninsula

R. Blakeney, A Boy in the Peninsula

A. Schaumann, On the Road with Wellington

G. Larpent, The private journal of F. Seymour Larpent

J. Gurwood, The Dispatches of Field Marshall the Duke of Wellington

My history of the 5/60th – Riflemen is available now from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and other book retailers, or direct from the publisher Helion & Co.