The popular misconception is that commissions and promotions in the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars were mainly gained via the purchase system. However, the demand for officers vastly outweighed the supply of those with the means to buy their way to the top. Overall only around 20% of promotions were actually paid for, although the proportion rose for the more senior ranks.

Most promotions were awarded by seniority, especially those following the death of an officer. Rising from the ranks was more common than is widely thought as well. The 5th battalion of the 60th regiment of foot was the first all rifle battalion of the British Army and was composed mainly of Germans, Dutch, Swiss and Poles, with a mix of British and foreign officers.

For those who thought themselves worthy of a commission or promotion the accepted method of was to write a memorial; a letter outlining why you merited advancement. These were then endorsed by your commanding officer, local commander or person of influence and forwarded to the office of the Commander-in-Chief of the army. These memorials have survived and are to be found in the WO 31 series at The National Archives at Kew. They provide great insights into the individuals and also the process of preferment and patronage.

Many of the officers of the 5th battalion were from mainland Europe and often cut off from their homes and families. They had to rely on their salaries and had no other income, which made purchasing promotions impossible. One such officer was John Galiffe. His letters often dwell on the slowness of his promotions and he was often purchased over by wealthier British officers. He spent many years as a captain before eventually becoming a brevet major in 1808. A brevet rank meant that within the regiment he was still a captain, and paid as such, but had the authority of a major to the rest of the army.

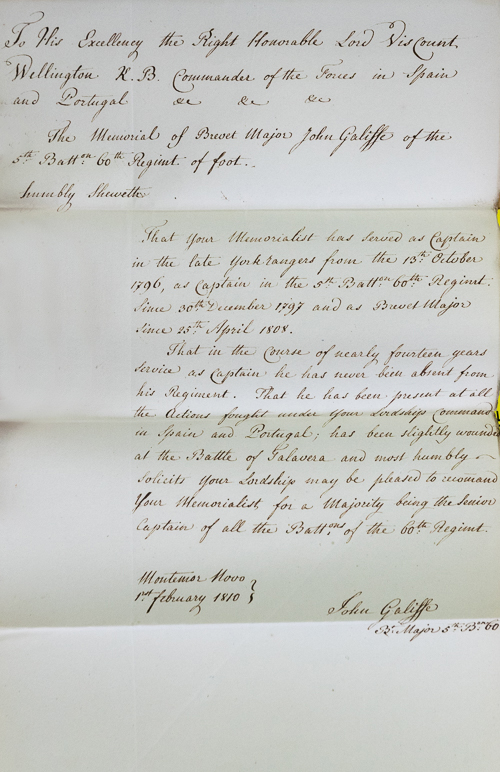

In 1810 he wrote a memorial and sent it to Viscount Wellington:

“The Memorial of Brevet Major John Galiffe of the 5th Battn. 60th Regiment of Foot.

Humbly sheweth

That your Memorialist has served as Captain in the late York Rangers from the 13th October 1796, as Captain in the 5th Battn. 60th Regiment Since 30th December 1797 and as Brevet Major Since 25th April 1808.

That in the course of nearly fourteen years service as captain he has never been absent from his Regiment. That he has been present at all the actions fought under your Lordships command in Spain and Portugal; has been slightly wounded at the Battle of Talavera and most humbly solicits your lordship may be pleased to recommend Your Memorialist for a Majority being the Senior Captain of all the Battns. of the 60th Regiment.

John Galiffe

B. Major 5th Bn. 60th.Montemor Novo

1st February 1810”

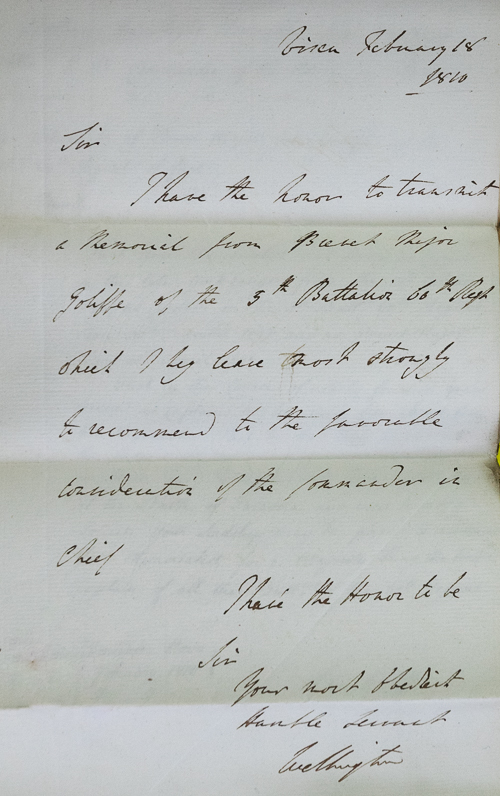

Wellington sent it on to the Commander in Chief, Sir David Dundas, with his endorsement:

“I have the honour to transmit a Memorial from Brevet Major Galiffe of the 5th Battalion 60th Regt. Which I beg leave most strongly to recommend to the favourable consideration of the Commander in Chief.”

Galiffe received the promotion and was gazetted major 15 March 1810.

Lieutenant George Zuhleke was another long serving officer of the 5th battalion who had managed to rise from Ensign to Lieutenant, and then made his case for a captaincy in 1809. He pointed out that due to various officers being absent or on staff duty he had commanded a company since 1802. He was wounded at Talavera but then captured by the French when the Spanish pulled out, leaving many of the sick and wounded behind. He was well cared for and taken to Madrid but managed to escape and return to Portugal. During his absence, a captain of the 3rd battalion of the 60th had died ‘in the hospital in which he was confined as a lunatic’ and Zuhleke’s application for a promotion was granted, but rather than leave Portugal for the West Indies, where 3/60th were stationed, he opted to become a Major in Portuguese service, joining the 2nd Cacadores.

It often helped to have a member of the royal family in your corner. The memorial for Lewis de Ingersleben included a letter from the Duke of Cambridge. Ingersleben had been a lieutenant in the Prussian army but following the reduction of that army after defeats by Napoleon and the Treaties of Tilsit he was one of many Prussian officers to seek British service. He joined the 5th battalion as an Ensign in 1810.

Memorials were not always successful though. Lieutenant Van Den Borgh, formerly of the Hompesch Hussars, asked to join the 5th battalion of the 60th and had the backing of the Duke of Kent but was appointed to another battalion of the 60th before entering Portuguese service.

Assistant Surgeon William McGillivray had served under Wellington when he commanded the 33rd foot in India, and used that connection to help him secure his appointment as surgeon in the 5th battalion in 1809. Sadly he died soon after taking up his post.

Surgeon Drumglold of the 79th wrote a memorial asking for a posting to a warmer climate and ended up exchanging with Suregon Beattie of the 5th battalion, then at war in Portugal, who desired service with a Scottish regiment. The climate was warmer but perhaps not healthier.

Memorials were a way for deserving officers to gain advancement, but it was also a system that was open to abuse and cronyism. There must have been many who could not obtain the assistance of a powerful patron and who languished in the lower ranks. However, good commanders like Wellington saw the value of endorsing competent and able officers rather than having vacancies filled by those with less experience but deeper pockets.

My history of the 5/60th – Riflemen is available now from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk and other book retailers, or direct from the publisher Helion & Co.