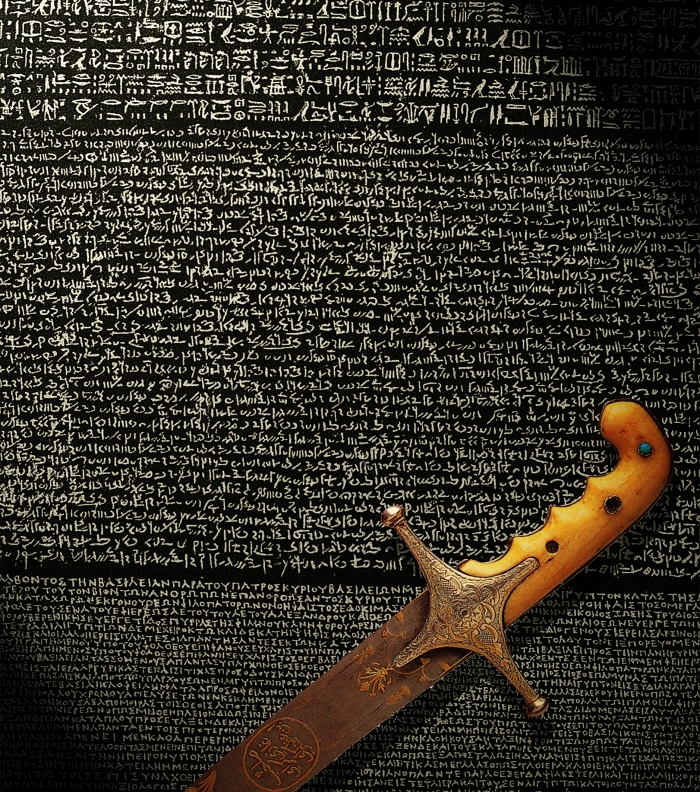

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most important archaeological artefacts ever discovered and has had pride of place in the British Museum for over two hundred years. However, it was discovered in Egypt by the French, not the British, and the tale of how it came to London rather than the Louvre involves war, skullduggery and tenacity.

General Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in July of 1798 and rapidly defeated the country’s Ottoman rulers. The Egyptian campaign was designed to be the first step in threatening Britain’s empire in India. With Bonaparte’s army were the dozens of artists and scientists of the Institut d’Égypte, whose mission was to catalogue and uncover the secrets of the Pharaohs. It wasn’t just intellectual curiosity that drove them. Science and engineering at the time was still very much based on classical teachings from Rome and Greece but the wonders of Egyptian knowledge were locked behind their impenetrable written language – Hieroglyphics.

A year after the invasion in July of 1798 near the village of Rashid in the Nile delta, known to Europeans as Rosetta, a party of French troops and local labourers was destroying an old wall to provide stones to improve the nearby Fort St Julien. It must have been hot, tiring and dusty work. In charge was Lieutenant of Engineers François Xavier Bouchard. You may not have heard of Bouchard but his name surely deserves to be up there next to Howard Carter as one of the heroes of Egyptology.

When one of his men found a curious stone covered in writing he could have just told them to break it up and carry on but he instantly recognised its significance. The stone wasn’t just covered with Hieroglyphs like most relics of the area, it also included ancient Greek and an another unknown script (Demotic). Bouchard informed his superiors, and the scholars of Institut d’Égypte soon took possession of the stone. In August 1798 Nelson destroyed the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile and Bonaparte himself left Egypt for greater things back in France.

The reason the stone was significant was that it appeared to have the same text repeated in each of the three scripts. If the hieroglyphs could be deciphered by using the Greek version then the secrets of Egypt might be at last uncovered. Copies of the stone were made and sent to Europe, and the find publicised in the Courier d’Égypte. The news soon reached Constantinople, and the British minister there – Lord Elgin. Elgin is, of course, famous for his ‘collecting’ of artefacts from Greece through his contacts in the Ottoman court. In 1801, when he was informed of plans for a British expedition to drive the French out of Egypt, so he made sure that his principal agent, William Richard Hamilton, was on hand to secure the stone and other French finds for Britain.

Hamilton was young and not long out of university at Oxford and Cambridge, but he had already served Elgin well in several diplomatic missions, as well as assisting with a little collecting. British troops landed near Alexandria in March 1801 under the command of the seasoned and popular General Sir Ralph Abercromby. The French were waiting for them on the beaches but they were driven back and the British were soon besieging Alexandria. Abercromby was mortally wounded in battle on 21st March when the French tried and failed to break the siege.

Command of the British army devolved to the less able and less dynamic General John Hely-Hutchinson who, nonetheless, led his troops slowly and steadily towards victory. Hamilton persuaded the general to add in a clause to the French surrender treaty specifically naming the Rosetta Stone and the other antiquities found by the Institut d’Égypte, to ensure that they fell into British hands, but the Institut d’Égypte fled as the British approached Cairo and took shelter in the still besieged city of Alexandria. They took the stone with them.

Alexandria soon fell as well though and Hamilton rushed into the city in search of the stone. The French weren’t going to give it up easily though. It was hidden amongst the baggage of the French commander General Menou in a warehouse near the harbour. Hamilton tracked it down and, with a party of gunners from the Royal Artillery, seized it. He found other artefacts scattered across the city including a large green stone sarcophagus in the hold of a French ship.

The stone was sent back to Britain in the frigate L’Égyptienne, herself a prize seized at Alexandria and soon to be commissioned as HMS L’Égyptienne. The stone arrived in February 1802 and was studied by the Society of Antiquaries. It was handed over to the British Museum later that year and has remained there ever since. It was, of course, the subject of intense study, and many attempts were made to decipher it. Thomas Young made significant progress but ironically it was a Frenchman, Jean Francois Champollion, who eventually cracked it in the 1820s.

I’ve been lucky enough to work on several projects with the British Museum, and it was reading the tale of the Stone’s discovery and capture that inspired my first novel, Forty Centuries Looking Down. It’s always interesting to uncover the ‘full’ story behind these iconic objects from history – there’s almost always more to be told than the details that most people know, and it often takes less digging to reveal them than you might expect.

References:

Lord Elgin & the Marbles – William St Clair

The Rosetta Stone – Carol Andrews

British Victory in Egypt – Piers Mackesy

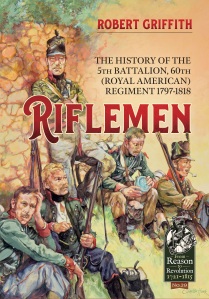

Available from Amazon or directly from the publisher Helion, which means I make a little more rather than Amazon getting all the profit!