If the Alien Office was the Napoleonic equivalent of the SOE then the Secret Office of the General Post Office was the Bletchley Park. Government surveillance and privacy may seem like very contemporary issues but the conflict between the two has been going on for centuries. Founded in 1653 the job of the Secret Office was to intercept, copy and decipher diplomatic, foreign and even domestic internal mail. During the political unrest and wars of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods its activities both expanded and became more vital to the security of the British state.

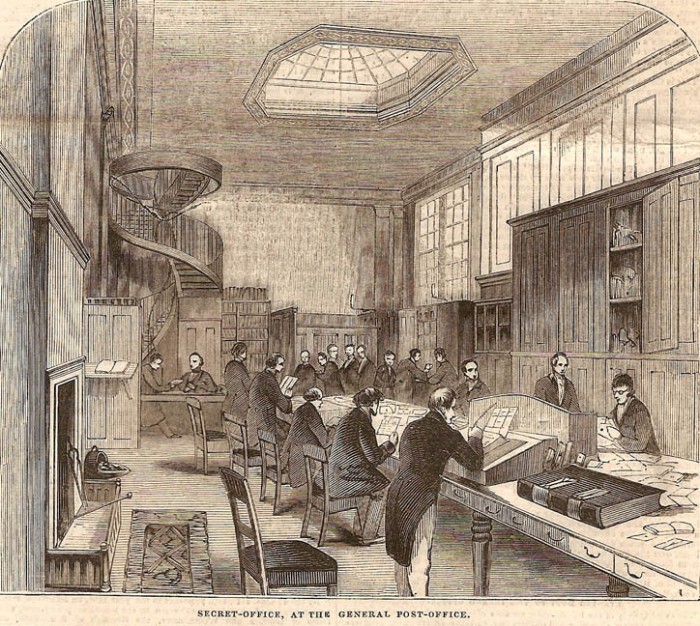

It was accepted practice at the time that diplomatic letters could be subject to interception. Many countries in Europe had their own versions of the Secret Office. Originally housed in three small rooms in the Foreign Office the office’s staff would receive bags of foreign mail twice day direct from the packet service that shipped letters all around the growing British Empire and Europe. They would have very little time to sort through the bags, identify anything of interest, open it, copy it and then reseal it before sending it on to the recipient. Forgers were employed not only to ensure that there was no evidence of tampering but also to occasionally create false letters and communiques.

Following the French Revolution the office concentrated on countering the risk of internal strife, including the rebellion of the United Irishmen. The system was not without safeguards though and a warrant for interception had to be obtained from the Home Secretary, however such warrants could be very broad targeting many individuals or even general crimes such as sedition or treason. Intercepted letters could then be used in court, for example one sailor pressed into the navy against his will wrote home to his wife with a plan of escape and found it being used against him at trial. The number of warrants varied with the amount of unrest. During 1812, at the height of a wave of Luddite protests, 28 were issued.

After 1798 the office refocussed its efforts on the war against France. Its staff were expanded to ten and it moved into offices within the post office on Lombard Street. In 1801 its annual cost was £5060, with its head being paid £1000 and even the doorman £50. However, its very existence was a closely guarded secret and few normal post office employees new it was even there. The intercepted intelligence was also very narrowly circulated, much like the ULTRA intercepts from Bletchley Park, to maintain security. Many diplomats and agitators were, however aware of the risks, and wrote in codes or with invisible inks. British diplomats used commercial bankers as messengers rather than trust the postal systems in Europe and many had their own enciphering clerks. British Ambassador to Naples Sir William Hamilton used his wife Emma, later Nelson’s mistress, to encode his correspondence. The Secret Office was also used as a conduit for clandestine communication with foreign diplomats and officials.

Intercepted letters in code were sent from the Secret Office to the Deciphering Branch, which was founded in 1703 by Oxford don Rev. Edward Willes. It seems that the Willes family had quite the knack for tackling codes and as late as 1790 a new Spanish code was giving Sir Francis Willes trouble.

Between them the Secret Office and the Deciphering Branch were often so successful though that British ministers were sometimes reading letters before their intended recipients but the office’s task wasn’t without its challenges. With the onset of hostilities diplomats were withdrawn and a source of valuable intelligence dried up. However, the office worked closely with its Hanoverian equivalent in Nienberg which aided in continental interceptions and shared intelligence. Also as the sheer amount of post increased over the period it became harder to find incriminating letters.

After Waterloo the office’s staff was reduced but its activities continued. The full extend of its activities were revealed in a scandal in the 1840s and a parliamentary inquiry followed. The opening of foreign mail was not an issue but it was the opening of internal post that proved controversial.

Sources

Regency Spies – Sue Wilkes

Secret Service –Elizabth Sparrow

Most Secret and Confidential: Intelligence in the Age of Nelson – Steven Maffeo

Available from Amazon or directly from the publisher Helion, which means I make a little more rather than Amazon getting all the profit!